How ‘Security Scorecards’ Advance Security, Reduce RiskHow ‘Security Scorecards’ Advance Security, Reduce Risk

CISO Josh Koplik offers practical advice about bridging the gap between security and business goals in a consumer-facing media and Internet company.

Bishop Fox’s Vincent Liu sat down recently with Josh Koplik, IAC chief information security officer, in a wide-ranging conversation about the all-too-common schism between business and security objectives, his innovative security scorecard, and why strong security will never be a strategic marketing asset for business. We excerpt highlights below. You can read the full text here.

Fourth in a series of interviews with cybersecurity experts by cybersecurity experts (Read first, second, third, fifth, and sixth).

Vincent Liu: Why do business and security people think differently about risk?

Josh Koplik: Understanding what makes a system secure is easy because it’s a technical problem. Deciding whether or not that’s worth doing from a business standpoint is more complicated. A lot of security people assume that security initiatives are always worth pursuing. If it takes zero resources – no time, no money, no anything – of course you’d do it. Every security improvement comes with a cost, and those costs are not always apparent or worth bearing.

VL: What do you, as a security professional, wish business people understood?

JK: I don’t think a lot of business people consider the cost of security events. The impression is that these breaches cost outrageous amounts of money, but I don’t think that’s the case. Even in the most high-profile examples, if you look at the breach costs as percentage of annual revenue or some metric that takes into account the size of the target to begin with, it’s not that bad. I also think breaches, in terms of real impact, get overstated as far as reputational impact is concerned.

VL: Are there times when you as a security executive would consciously accept risk?

JK: Security people would do well to accept risk, have a process for accepting risk, and make their business colleagues comfortable with accepting risk or paying for mitigation.

If we have this business that is under-performing, it’s easy to look at the balance sheet of that business and know whether spending $100,000 on a pentest is worth doing. This is one place where CISOs can run into trouble.

Once you get to the point where you are no longer under a CIO, you’re no longer part of a technology organization, and you’re having regular conversations with your CFO, your CIO, with your heads of your business lines, those conversations become easier. Your CFO may not understand stack overflows and intrusion prevention systems, but he knows numbers. So you can say, “Here’s a thing. On a scale of 1 to 10 in terms of importance, I give it a 7. And it costs $150,000.”

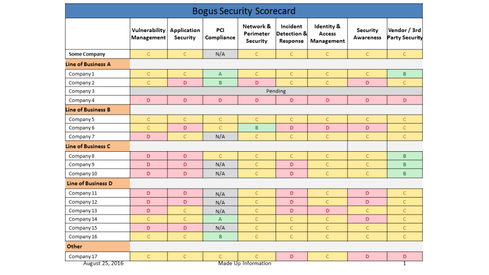

VL: Tell us about your security scorecard? Do you actually give out grades?

JK: I use people’s inherent competitive nature in this situation. I issue grades, which makes people work harder so they can beat the other guy.

VL: What does it look like and how does it work?

Figure 1: Source: IAC

Source: IAC

JK: Basically, businesses are listed down the left side. Then, security domains are listed at the top. In each little box, there is a letter grade and corresponding color code. Bs are green, Cs are yellow, Ds are red, and that’s it! That’s the scorecard.

Behind the scenes, there’s criteria; in other words, it’s descriptive. To earn an A in vulnerability management, you have to do this series of things. It’s not long, you can read the criteria for the entire seven domains in fifteen minutes. The grade levels are slightly different-worded versions of the same thing. Whereas a B might state “most,” a C will state “some.” There is enough room for interpretation that you can wiggle between grade levels, but not enough room that things look fake. It’s an A, B, C, D scale; there is no such thing as an A-. I have enough trouble differentiating between B and C as is. ABCD I can describe well.

Because it’s simple, people at the executive level can understand it at a glance. You can easily present this to a CEO. If a business wants to grow, they will want to do something about poor grades. However, if you go to a struggling business with a bunch of Ds, they’ll shrug and say, “That is the least of our problems. We don’t have any revenue.”

VL: When I spoke to Rich Seiersen at GE Healthcare he said that some things are unnecessary because they don’t progress the conversation. Instead, they end up wasting time and detracting value. What you’re really doing with these scorecards is trying to drive change or to start a conversation, isn’t it?

JK: Grades don’t make you more secure; they need to reflect practices that you are doing that actually make you more secure. They define what those things are and whether or not they are being done. You need to trace anything you are measuring back to on-the-ground activities that improve security. If you can’t, I question what you are measuring.

VL: Are there downsides to your scorecard? (Continues on page 2.)

JK: Absolutely. You can put a lot of effort in and not move your grade. I have a few different ways that I acknowledge those bits of progress. I give brownie points on the scorecard like, “investments have been made in this area,” etc. We’ve had to stay regularly involved with the people who are responsible for implementation. We need to keep them honest because it’s not that they are being maliciously deceptive; they are putting a positive spin on things. The other thing people do is that they give you their optimistic six-months-from-now answer. People need to answer in the present tense.

VL: How do you handle the situation where you have trouble communicating to people who are not primed to worry about security?

JK: I don’t think those people exist in 2016. What people do exist are those who feign that they are absolutely committed to security and they tell you everything you want to hear … and then they don’t do anything. I don’t think this is malicious. Security just falls on that long list of things that they want to do and then they have to make business decisions. Your conversation with them was reduced to three line items on their budget.

VL: So how do you get that crucial buy-in from executives? Is security ever an asset to them?

JK: I frame it as there is a minimum level of security necessary to run a consumer-facing web company in 2016, and we need to make sure our security practices are up to that level. I explained this to our CEO and the CEO of one of our subsidiaries as well and asked if they see security as a marketable feature. They both said there’s no way to use security strategically from a business or marketing standpoint.

Their reasoning was best explained as: “It’s a slippery slope, and dangerous road to go down to say we’re secure because you are creating liability for yourself. If you ever do have an incident, then you have the problem that you claimed you were secure and you were not.”

Personality Bytes

Figure 2: Josh Koplik, Chief Information Security Officer, IAC

Josh Koplik, Chief Information Security Officer, IAC

Start in security: I grew up in the Midwest, and in 1994, all I wanted was to access the Internet. As I grew older, I landed jobs in tech, and the Internet became more accessible. I did some help desk stuff in college, and I worked as a C developer at a startup in the late ‘90s. I preferred doing more infrastructure-type things. I eventually moved to Fidelity as a security engineer.

Networks versus application experience? Applications because they are harder to learn if you don’t have the background. To understand application security, you have to understand what’s happening everywhere else.

Best career advice to security engineers: As a technician, you are bound to hit a ceiling so at some point, you have to step up and take on leadership roles, learn the ways to navigate an organization, work with constituents, and build support for initiatives.

Advice for a CISO or CSO moving into a newly created role: Don’t build relationships only with the C-level people. Build them with the people who are responsible for implementation, too. When they come to me, I always urge them to help me understand where they are having issues [because] we have to tell the security story together. With the C-level, ask them what they want to see. Keep things simple. Only measure something that you can accurately measure. Only tell a story if you can tell it to the end.

Biography: Joshua J. Koplik joined IAC/InterActive Corp. in September of 2014 as its chief information security officer. In this capacity, Koplik oversees information security across IAC and its broad portfolio of subsidiary businesses, which include Match, OKCupid, HomeAdvisor, and Tinder. Koplik previously served as director, global information security for Home Box Office, Inc. from 2009 to 2014, where he was responsible for information security & compliance for HBO’s global enterprise. Prior to joining HBO at its New York headquarters, Koplik served as director of technology risk management for Fidelity Investments in Boston. Mr. Koplik completed his bachelor’s degree in computer science from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and has held a CISSP certification since 2005.

About the Author

You May Also Like

Uncovering Threats to Your Mainframe & How to Keep Host Access Secure

Feb 13, 2025Securing the Remote Workforce

Feb 20, 2025Emerging Technologies and Their Impact on CISO Strategies

Feb 25, 2025How CISOs Navigate the Regulatory and Compliance Maze

Feb 26, 2025Where Does Outsourcing Make Sense for Your Organization?

Feb 27, 2025