The Race to Hack a Satellite at DEF CONThe Race to Hack a Satellite at DEF CON

Eight teams competed to win cash, bragging rights, and the chance to control a satellite in space.

August 13, 2020

At DEF CON 27 there was a tantalizing promise: A space-based capture-the-flag competition at DEF CON 28, featuring actual satellites to be controlled. Then came 2020.

Hack-a-Sat, as it came to be called, was still on. In the spring, more than 6,000 competitors virtually gathered, self-organized into more than 2,000 teams. In May they competed in a series of challenges, and by May 24, eight teams had risen to the top. At DEF CON 28, they spent two days working through five challenges with several rewards at stake. One (and a big one at that) was bragging rights. Another was a shared of a $100,000 prize purse. And third was the chance to have a solution uploaded to an actual, operational satellite and have it dance to the tune called by the winning team.

Figure 1:  Image courtesy DEF CON Communications

Image courtesy DEF CON Communications

The eight teams, with members from around the world, were: Poland Can Into Space, FluxRepeatRocket, AddVulcan, Samurai, Solar Wine, PFS, 15 Fitty Tree, and 1064CBread.

On Friday morning, August 7, they began the competition, which was part of the Aerospace Village at DEF CON.

Floating on Air

Unlike many capture-the-flag (CTF) competitions, Hack-a-Sat had a physical component for each team. The sponsors had purchased a series of off-the-shelf training satellites featuring a "standard" guidance navigation and control system (GNC) and a custom Artix 7 FPGA- and Raspberry Pi-based board for onboard and payload systems. According to the team that ran the competition, code from the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA was used on the two boards, with the off-the-shelf board chosen for its rapid access to sensor and control surfaces, and the custom board designed to be far more interesting from a CTF perspective.

The physical elements came from the "flat sat" training satellites that were platforms for the electronic components. These earth-bound physical simulators were mounted on air-bearings so they could move without resistance and simulate various elements of the scenario. The competition lab also had moving radio transceivers for each team, to simulate moving communication issues, and a virtual moon (along with other visual targets).

5 Challenges

The scenario for the contest allowed for a wide variety of challenges: A satellite has been attacked and compromised by an attacker, and is now spinning out of control. The teams need to regain control of the satellite.

To do that, they had to complete five challenges - four that were scored based on order to arrive at a solution and time required, and one that was pass/fail.

Challenge 0: Gain control of the satellite communications ground station.

The adversary had obtained access and locked others out, so teams had to use a network to access to the station.

Challenge 1: Attempt communication with the satellite spinning out of control.

They then had to regain communications with the satellite.

Challenge 2: The satellite's guidance navigation and control system (GNC) "went offline."

Teams had to repair it as quickly as possible to stop the the satellite's spinning. This was a challenge in which the satellite's physical reality became important: Each flat-sat had only so much battery power for the day, and solutions that used too much power could leave the teams unable to solve subsequent challenges until after the satellite had recharged overnight.

Challenge 3: The satellite has stopped spinning but can't communicate with the payload module or imager.

This brings up an important question: what else might be damaged? Teams had to restore communications to the payload module.

Challenge 4: Restore normal operations of the payload module to then control the imager.

Challenge 5: The teams have regained control, but now must prove it by taking an image of the moon in the lab.

This challenge was pass/fail and was important for two additional reasons. First, teams had to pass this test to be eligible for podium placement at the end of the challenge. Next, one team would be selected to have their solution uploaded to an actual satellite to see whether it could get an image of the actual moon.

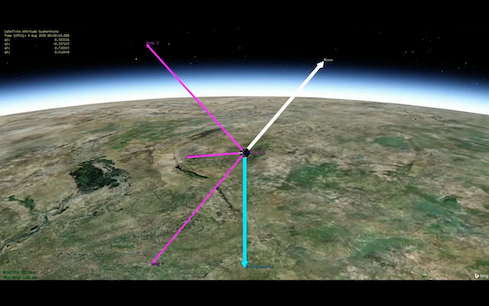

Figure 2:

Primary vectors required for proper orientation of the satellite to take an image of the moon.

Image courtesy DEF CON Communications

Solving the challenges involved a combination of traditional communications hacking, diving through documentation, understanding orbital mechanics and flight controls, and hardware hacking through exploiting undocumented input and output mechanisms. Every hour throughout the two days of the competition there was an update showing a leaderboard with comments on the progress (or lack) by the various teams, and explanations of the challenges and solutions.

Story continues on the next page

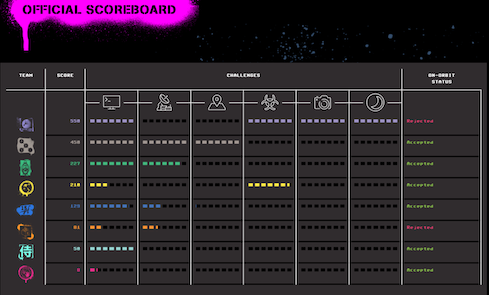

Winner and Losers

By the end of the challenge, six teams had completed Challenge 5, leaving two teams ineligible for a podium position. In a twist, one of the ineligible teams - Solar Wine - had the highest total points for the competition. While Solar Wine could claim bragging rights, PFS took the top podium step and the $50,000 top prize. Poland Can Into Space was the team chosen to have its Challenge 5 solution uploaded to a satellite, and it was successful in taking an image of the moon with a normally earth-facing satellite.

Figure 3:

The final scoreboard for Hack-a-Sat 2020

Image courtesy DEF CON Communications

Prizes were (virtually) presented by Will Roper, assistant secretary for acquisition, technology and togistics at the US Air Force; and Brett Goldstein, director of the Defense Digital Service. Their participation showed the importance that the DoD now assigns space-based cybersecurity issues.

According to Roper, while the DoD was present at DEF CON in 2019, their participation in Hack-a-Sat was very successful. "There were more interactions for Department of Defense in the first day this year than we had in the entire Con last year," he said, adding that there were nearly 15,000 visitors to the Hack-a-Sat website with an additional 5,000 visiting a virtual-reality version of the site.

Figure 4:

In the end, Poland Can Into Space took a satellite image of the moon.

Image courtesy DEF CON Communications

For the Air Force, Roper said, there was a clear lesson: "This is something we should have been involved in a long time ago."

Planning for next year's hack-a-sat competition should, organizers said, begin within the next few weeks.

Related Content:

Read more about:

Black Hat NewsAbout the Author

You May Also Like

_marcos_alvarado_Alamy.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)