How To Hack A Brazilian Power CompanyHow To Hack A Brazilian Power Company

The recent "60 Minutes" story claiming hackers had caused power outages in Brazil was (likely) bogus, but that doesn't mean hackers can't do this. The story got widespread coverage in the Brazilian press, which meant hackers there were suddenly interested in the subject. And just days later, chatter appeared on Brazilian hacker Websites expressing interest in ONS, the Website of Brazil's national power grid operator.

The recent "60 Minutes" story claiming hackers had caused power outages in Brazil was (likely) bogus, but that doesn't mean hackers can't do this. The story got widespread coverage in the Brazilian press, which meant hackers there were suddenly interested in the subject. And just days later, chatter appeared on Brazilian hacker Websites expressing interest in ONS, the Website of Brazil's national power grid operator.A member of the Brazilian press called me and asked if I could confirm whether there was a danger. I confirmed it: The Website had obvious vulnerabilities that any teenager could hack.

The first was the "robots.txt" file. This is a file that tells search engines to ignore parts of a Website. It's the first thing hackers look at: If you don't want part of your Website appearing in search results, then it's likely sometime hackers would be interested in. This was the file at http://www.ons.org.br/robots.txt:

User-agent: *

Disallow: /agentes/agentes.aspx

Disallow: /download/agentes/

According to the underground chatter, the URL http://www.ons.org.br/agentes/agentes.aspx contains all sorts of internal applications that should not be publicly available. It also contains documents and manuals that would teach outsiders a lot about how ONS works.

Picking one of the applications at random, you can enter a username of "asdf'asdf" (with a quote character in the middle). The quote character is a test to see whether the application is vulnerable to SQL injection. The request will be rejected, but what's important is how it will be rejected.

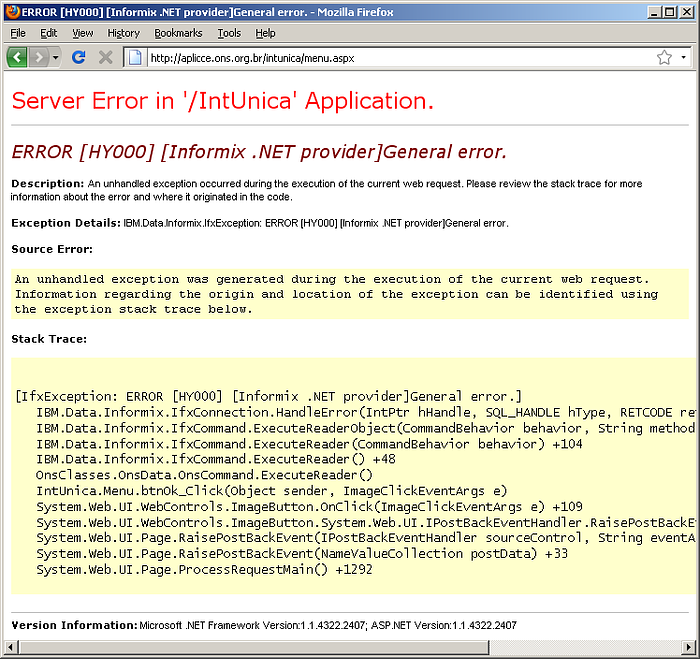

After doing this, you would see the result below:

To a high degree of probability this indicates that the application is vulnerable to SQL injection. However, this is a variant known as "blind" injection: While you can send bad SQL queries to the Website, you cannot see their results. This means that while the Website is vulnerable, it's not something an average teenager would be able to exploit.

Elsewhere on the Website is a registration page. Filling it out and giving a company name of "asdf'asdf" produces the following error message:

Erro ao Cadastrar AgenteLine 1: Incorrect syntax near 'asdf'. Unclosed quotation mark before the character string ',0,')'.insert into cadastro_agente (nm_cod_pk, vc_nome, vc_sobrenome, vc_email, vc_endereco, vc_estado, vc_cidade, vc_ddd_telefone, vc_telefone, vc_sexo,nm_cod_funcao_fk, dt_nascimento, dt_cadastro,vc_info, vc_tratamento, vc_empresa, vc_cep,vc_site, vc_email_secundario, nm_cod_tipo_fk, dt_alteracao, nm_permission_mkt, vc_password, nm_numero, vc_complemento) values(13256, 'Winnie', 'Thepoo', '[email protected]', '', 'AC', '', '', '', 'M', '4', '1980-1-1', getDate(), '1', 'Poobear', 'asdf'asdf', '-', '', '', '2', getDate(), 1, 'letmein', 0, '')

This again indicates SQL injection. However, in this case, the injection isn't blind: The error page repeats the underlying SQL query. This sort of injection would be much easier for hackers to exploit.

SQL injection is the most common vulnerability on Websites. Most security professionals add a quote ' mark to their Web input whenever they visit a new site, curious to see whether they will get an error message (like the one above). It's not 100 percent proof that the system is vulnerable, but in my experience doing pen testing, more than 95 percent of the time such a vulnerability will lead to a full compromise of the Website.

ONS was notified last week of this problem. They've confirmed that, indeed, its Website was hacked. It claims to have fixed the SQL injection problems and that there was no danger because there was no connection between its Website network and back-end control network. In my experience, that claim is likely wrong. Data has to be transferred somehow from the power transmission grid to the front-end network. Once a hacker breaks into the network, he can usually find that connection.

My point with this post is to give details, not to scare. Power grids are still more likely to have accidental failures than hacker attacks. If Al Qaeda or the Chinese wanted to create power outage, then they could do so more effectively with 10 well-placed bombs. Hacking is a threat, and it's one that most power companies do take seriously, but it's not something worth panicking about.

Robert Graham is CEO of Errata Security. Special to Dark Reading

About the Author

You May Also Like