Post 9/11: Five Years Of IT Promise And Failure

Sept. 11, 2001, spurred IT innovation and integration like no other event in history. Driven by fear, defiance, and inspiration, industry and government quickly promised to correct the conditions--including siloed data repositories, incompatible communications systems, and lax security practices--that allowed the terrorist attacks to be executed with such deadly precision. How far have we come in five years? Let's put it this way: We've got a long way to go.

Sept. 11, 2001, spurred IT innovation and integration like no other event in history. Driven by fear, defiance, and inspiration, industry and government quickly promised to correct the conditions--including siloed data repositories, incompatible communications systems, and lax security practices--that allowed the terrorist attacks to be executed with such deadly precision. How far have we come in five years? Let's put it this way: We've got a long way to go.Businesses, law enforcement, and government--in particular, the Homeland Security Department, formed in July 2002 from nearly two dozen government agencies in direct response to 9/11--have shown both promise and disappointment with regard to their IT initiatives. They've formed and funded crucial data collection and sharing programs, yet the execution of several of these have run afoul of privacy rights groups and even the courts. The National Security Agency's surveillance program was not only greeted with uneasiness by the public, but it was shot down last month when U.S. District Judge Anna Diggs Taylor ruled that the program violates the First and Fourth Amendments by monitoring communications without warrants.

In a move to improve access and information sharing among immigration and law enforcement officials, Homeland Security this week announced it has launched the first phase of a proposed three-phase program to promote interoperability between the U.S. Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-Visit) program's Ident database and the FBI's Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System database. The goal is to provide state and local law enforcement officials with access to immigration history based on biometric and biographic information through a single biometric submission to these databases. Subsequent phases will increase the amount of data that Homeland Security and Justice exchange and provide law enforcement and immigration officials with a complete view of a person's criminal and immigration history.

Data collection and integration make up a pervasive thread that ties together all post-9/11 efforts to improve national security. They're the foundation of the Homeland Security Department's controversial Secure Flight program, which remains grounded thanks to unanswered questions regarding what data will be collected from passengers, how that data will be used, how it will be secured, and how decisions based on that data can be appealed.

Homeland Security's Registered Traveler program has done better, attracting thousands of participants. Passengers volunteer to undergo a federal background check in order to obtain an ID card encoded with fingerprint and iris images that speed them through airline check-ins at participating airports, which include Orlando International Airport and British Airways Terminal 7 at New York's JFK International Airport and will soon include Norman Y. Mineta San Jose, Indianapolis, and Cincinnati International airports once these locations get approval from the Transportation Security Administration. Bus and train travel have no such program, even though both have been targets of subsequent terrorist attacks.

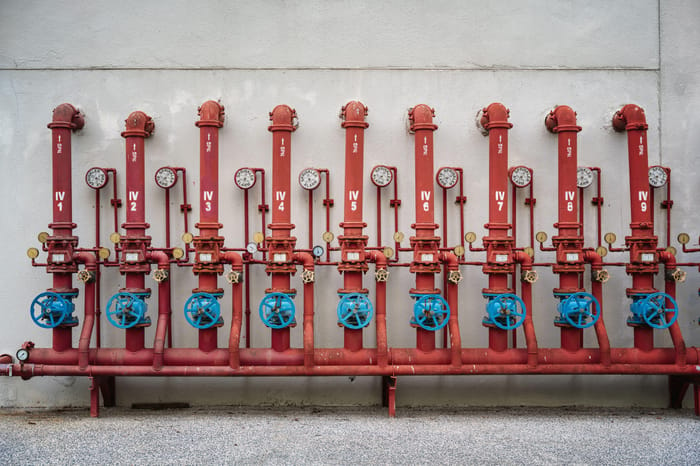

In evaluating government and industry efforts to protect the critical infrastructure that keep the lights on, the transit systems moving, and the Internet chugging along, it's clear that there have been many programs launched over the past five years to improve security, but much less clear whether those programs are up to the task of protecting the country from attack, real or cyber.

True, we've yet to have a crippling attack against a nuclear power plant or a major shipping port, and the Internet has proven itself for the most part resilient against a variety of worms and viruses, but the feds haven't clearly laid out requirements for securing critical infrastructure, and there's no clear protocol in place for responding to a massive cyberattack. It may not be fair to say we've been lucky, but it's entirely accurate to say our critical-infrastructure defenses haven't truly been tested.

It's easy to give the government poor grades because it hasn't come up with a clear, consistent policy for dealing with critical-infrastructure threats, but private-sector industry is equally, if not more, complicit in this failure. Given that private-sector businesses own more than 85% of the nation's utilities, transportation facilities, and other critical infrastructure, nothing short of a law would force them to devote time and money to address these problems. Shareholders would rather see these companies invest in areas that generate profits rather than those areas devoted to security.

The safety of the Internet as a piece of critical infrastructure is much less certain. In a July report, the Government Accountability Office noted that federal laws and regulations that address critical-infrastructure protection, disaster recovery, and the telecommunications infrastructure provide broad guidance that applies to protecting the Internet, but it's not clear how well the country could recover from a major Internet disruption. While the Internet originated as a U.S. government-sponsored research project, the vast majority of its infrastructure is currently owned and operated by the private sector.

The lack of a unified blueprint for public- and private-sector coordination in the first 72 hours of an emergency leaves a gaping hole in the ability to respond to any attack against the national infrastructure, says James Gilmore, who was governor of Virginia on 9/11 and chaired the Gilmore Commission assessing the country's capability to respond to terrorist attacks. Partnerships between public and private entities are the only way prevention and, if necessary, response can be achieved. There's a lot at stake if businesses aren't able to use the Internet or if their systems are disrupted, he adds. "If you disrupt private-sector business, you disrupt the United States."

Perhaps the anniversary of that dreadful day will stir in government and business leaders that sense of purpose they felt five years ago, before politics and posturing slowed the progress of so many important programs. It's time to recapture that feeling we had when the dust finally began to settle, the markets reopened, and passengers once again took to the air, when we rolled up our sleeves and prepared to show the world what we were really made of.

Read more about:

2006About the Author

You May Also Like

_KonstantinNechaev-Alamy.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)