The Changing Face Of Advanced Persistent ThreatsThe Changing Face Of Advanced Persistent Threats

APTs and targeted attacks are becoming more mainstream. Is your enterprise ready?

August 15, 2013

Download the Dark Reading August digital issue

Download Dark Reading's August 2013 Digital IssueEarlier this year, a small aerospace company asked AccessData, a forensics and security firm, to investigate how its data had ended up on file-sharing service Box.com. The firm, which AccessData declined to identify, had received a call from the file-sharing service's sales team asking if it wanted to upgrade its accounts to Box's enterprise service.

The only problem: The aerospace company had never signed up for Box.

AccessData's investigation revealed that malware had compromised the systems of six employees at the company and created accounts for each of them on the cloud service. From there, the attackers uploaded and downloaded data. "Traffic going to Box.com seems pretty innocuous, so from the attacker's perspective, this is brilliant," says Jordan Cruz, senior forensic consultant for AccessData.

This type of targeted attack, sometimes filed under the heading advanced persistent threats (APTs), is increasingly being used to gain access to proprietary and confidential enterprise data. Attackers are refining their tactics, sometimes using public cloud services to bypass monitoring that flags suspicious traffic. AccessData isn't the only security company to identify such tactics; threat intelligence firm CyberSquared announced last month its discovery that a Chinese espionage group, known as the Comment Crew or APT1, had used Dropbox as an intermediate online cache for delivering malware.

The increasing sophistication of APTs is no surprise. While criminals first used targeted attacks to compromise important or hard-to-breach targets, these low-profile, high-impact operations have become the calling card of attackers targeting intellectual property and nations' top-secret data. In the past five years, targeted attacks have been on the rise, and attackers continue to improve their methods of reconnaissance, exploitation and mining of victims' networks in a variety of ways. Moreover, the number of nations developing cyber operations is expanding beyond the United States, China, Russia and the half-dozen other nations -- such as the United Kingdom and Israel -- that pioneered online intelligence-gathering operations. Operation Hangover, a recently discovered espionage network aimed at Pakistan, Norway, the United States and China, among other nations, appears to come from groups in India. And, a number of attacks on South Korean infrastructure targets have the hallmarks of North Korean cyber attacks. In addition, attackers are refining their techniques and expanding to targets that were previously assumed to be below the radar.

APTs are also becoming more common. Using off-the-shelf attacks and techniques such as Poison Ivy and the Black Hole exploit kit, even less-skilled attackers may successfully penetrate the defenses of most firms they target, says Liam O'Murchu, manager of security response for Symantec's North American operations. "With some of these targeted attacks, even though they are called 'advanced persistent threats,' the tools they are using are not all that sophisticated," O'Murchu says. "The vastly advanced nature of these attacks is the part that allows them to get into the targeted company -- zero-days and the like. Once they get in, they use normal, everyday tools."

Aggressive Diplomacy

One of the most significant trends in APTs is their use by developing nations. While China is the Asian dragon leading the charge, other countries -- from Iran to Malaysia to nations in Africa and South America -- are creating their own groups to access sensitive information from other countries and intellectual property from global corporations.

The aforementioned accessibility of hacking tools and the potential rewards to be gained by developing nations from spying on more industrialized countries combine to make cyber espionage the rule, not the exception, in nation-state operations, says Richard Bejtlich, chief security officer for Mandiant.

In many cases, developing nations are first exposed to cyber-espionage tactics as victims when they're targeted by larger countries seeking intelligence. Those smaller nations quickly adopt the same tactics, popularizing cyber espionage as a generally accepted method of gathering information. Iran, for example, started boosting its own cyber-operations capabilities and is becoming a "force to be reckoned with" after being targeted by the Stuxnet and Flame viruses, Gen. William Shelton, the U.S. Air Force's top cyber commander, told reporters earlier this year. North Korea has begun boosting its cyber capabilities, citing attacks from the United States and South Korea as the motivation.

Widespread attacks coming from China have also elicited responses from victims. China has used cyber espionage to gather intelligence on African and South American targets, putting pressure on those nations to develop their own additional cyber capabilities, says Mandiant's Bejtlich. "This idea of revving up your economy by stealing other people's research and then putting that into your own development is going to become more popular," he says. "And getting that information by digital means is the cheapest, fastest, most accurate way."

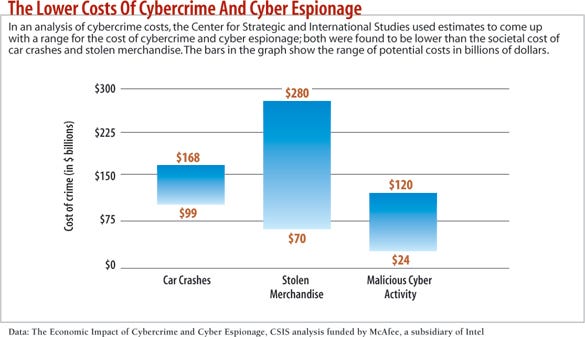

Tracking down groups that create and launch APTs is always difficult. Threat-intelligence companies aim to attribute attacks to certain groups, but it's very difficult to tell whether the group is working alone or on behalf of a government or company, says Pat Calhoun, senior VP at security firm McAfee, a subsidiary of Intel. "We have worked with a lot of law enforcement agencies, and in some cases we've been able to track attacks down to a group of well-funded individuals," Calhoun says. "But who is funding them is difficult to determine."

Digital trails left by attackers may lead to government agencies, or to companies or hacking groups for hire, says Dmitri Alperovitch, co-founder and CTO of security services firm CrowdStrike. "In this country, you have defense contractors, so it shouldn't be a surprise," Alperovitch says. He refers to these organizations as "the Blackwaters of cyber -- defense contractors building exploits and malware and even conducting operations on behalf of the government."

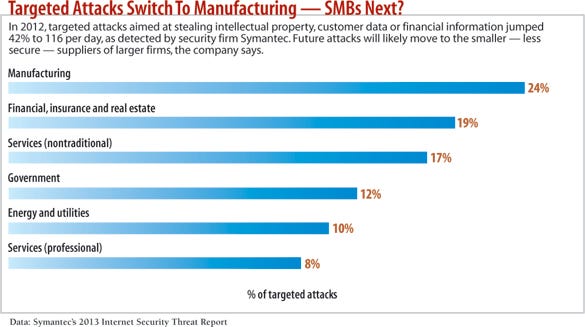

Targeting The Little Guy

As larger firms bolster their defenses against APTs, nation-state and other threat actors have moved on to target smaller companies. After all, many SMBs are suppliers to larger companies and government agencies but have fewer security resources, making them excellent gateways. In other cases, small companies have their own valuable intellectual property but fewer defenses than their larger counterparts, says AccessData's Cruz.

"Their IT department is usually only one guy," Cruz says. "The type of resources they have to monitor and respond to attacks is just not there."

In another case investigated by AccessData, a nanocomposite materials firm of fewer than 20 employees -- a company whose technology is used in a wide variety of industries -- found that its systems had been breached at the end of 2012. "It's a small company, cutting-edge technology, and they don't have the resources to defend against attacks," Cruz says.

Data from security firm Symantec confirms the trend toward attacking smaller firms. In 2012, companies with 250 or fewer employees accounted for 31% of the volume of targeted attacks Symantec detected, up from 18% in 2011, according to the company's Internet Security Threat Report. Together, small and midsize businesses -- those with fewer than 2,500 employees -- accounted for half of all targeted attacks in both 2011 and 2012.

[CORRECTION: The following two paragraphs have been updated to correct information on the timing of a recent trend in attacks on non-governmental organizations. The decline has only occurred in recent months, according to Kurt Baumgartner of Kaspersky.]

An interesting note: While attacks targeting intellectual property have increased, the focus on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as pro-democracy and human-rights activists, has waned in the last few months, says Kurt Baumgartner, a senior researcher with Kaspersky Lab. Three years ago, attackers whose goals appeared to align with the Chinese government conducted attacks against pro-democracy and civil rights movements. In the year following the discovery of GhostNet in 2009, reports of attacks on such NGOs skyrocketed. But now they seem to be fading, Baumgartner says, even as targeted attacks continue to pound away at military and defense-related organizations around the world, government agencies of all sorts, and commercial enterprises.

Baumgartner did not have a theory why NGOs have been targeted less in recent months.

Many charity groups do not have the expertise to detect the attacks, which could lead to a decline in reports. In addition, other NGOs may be spending more effort hardening their networks.

Exploits Blend In With The Everyday

Attackers are becoming more crafty about merging exploits with common, everyday traffic to escape the notice of defenders, observers say. In addition to using file-sharing services such as Dropbox and Box, they've started using compromised but trusted websites to infect targeted companies. Known as "watering hole attacks," this approach abuses the trust that targeted employees have in sites they use frequently.

"We will see more utilization of trusted services and creation of misplaced trust," says Lance James, head of intelligence for threat-intelligence firm Vigilant, now a division of Deloitte. Watering hole attacks, such as those targeting U.S. policymakers through the compromise of the Council on Foreign Relations' website in December 2012, could help spies stay under the radar of most defenders. The attacks compromise a website that victims are known to visit -- the watering hole -- and then target visitors that match certain criteria.

Companies should expect that the technique will be broadened to be used by government agencies looking to surveil certain groups, and they will set up their own watering holes, says Snorre Fagerland, lead researcher with software security firm Norman Shark. "You set up a website that is sympathetic to the cause, and then you monitor who is attracted to the content," Fagerland says. "That is more about surveillance of the people than it is about intrusion."

Such attacks are difficult to defend against because they exploit the trust users have for certain brands and services, experts say. While education can help, training will not eliminate the threat, says CrowdStrike's Alperovitch. Furthermore, allowing attackers to repeatedly lure users to click on a link will eventually lead to a successful compromise, he says. "You cannot have a situation where you allow it to be free [for the attackers] to try," he says.

Because watering hole attacks use trusted websites, security systems that identify potentially malicious sites based on reputation are unlikely to work. Some defensive firms, such as CrowdStrike, recommend focusing on the adversary and adopting strategies that raise the cost of attacking. For example, create decoys so attackers can't easily identify valuable data.

Confounding Researchers

While attackers have found subtler ways to infect targeted companies and users, advanced actors are also focused on avoiding detection. Criminals have long used "packers" to obfuscate their code by packing it tightly with other code. But more subtle attackers have moved to custom obfuscation or, ironically, no obfuscation at all, because heavy obfuscation is one of the signals that defenders use to identify malware. In addition, some attackers are using simple methods to confound automated analysis systems, as well as the researchers who do in-depth analysis of malware. Since automated systems can run suspected malware for only a certain -- typically short -- duration, attackers are increasingly developing malware that waits a specific amount of time or for a certain human action, such as a mouse-click, before springing into action. "When we discover the techniques that [attackers] are using, they change them," says Aviv Raff, CTO for security service Seculert. "They are using tools that are trying to bypass traditional security solutions."

These methods of obfuscation and delay have enabled some APTs to remain viable far longer than most other types of attacks. One malware variant, known as Comfoo, has been used for more than seven years by a group of attackers that Dell SecureWorks has dubbed the "Beijing Group" to attack more than five dozen firms and steal information. Selective attacks, encryption and low-profile command-and-control communications have kept Comfoo under the radar of most security analysts. Dell SecureWorks discovered the attack in 2011 and, by reverse engineering the listening servers for the espionage network, found out who was being infected. "We're seeing a small snapshot of a larger picture," says Joe Stewart, senior malware researcher with Dell SecureWorks' counterthreat unit. "You can't see the data exfiltration, but you are intercepting the initial login."

Critical Infrastructure In The Crosshairs

With its initial targeting of Iran's nuclear research facilities, the Stuxnet virus focused world attention on the dangers of a cyber attack on critical infrastructure. So far, however, damaging attacks on infrastructure are rare. In August 2012, attackers corrupted the hard drives on 30,000 computers at Mideast oil conglomerate Saudi Aramco in an attempt to hinder oil production. Several times in the last three years, attackers have compromised South Korean servers and, after initiating denial-of-service attacks or data exfiltration, deleted data on the systems. While such data wiping is destructive, it falls short of the seriousness of a Stuxnet-type attack, says Symantec's O'Murchu.

"It is easy to write a Trojan to wipe a hard drive -- it's an easy way for people to make noise -- and that activity could continue in the future," he says. "More targeted attacks like what we saw with Stuxnet are unlikely, however, unless something political is going on, like a war." Still, energy utilities and industrial control systems are so vulnerable and slow to plug the flaws in their systems that attackers will likely test their capabilities against them, says Kaspersky's Baumgartner. Already, researchers have pointed out serious vulnerabilities in these systems -- and the Shodan Internet port-scanning database has revealed how often those systems are connected to the Internet.

"Because critical infrastructure around the world is widely thought to be lagging a decade behind in security practices, there seems to be much more future risk there," Baumgartner says. "The [industrial control system] space is currently a strong attraction for some of the same attackers finding new motivations and some new attackers altogether."

Industrial control systems often can't be easily fixed, says Andrew Ginter, VP for Waterfall Security Solutions, a maker of unidirectional gateways for industrial networks. While business networks must adapt to aggressive change, utility and industrial-control networks are focused on stability, and that's a problem in responding to attacks. "How do you manage a reliability-critical network for a multibillion asset?" Ginter says. "You focus on engineering change control; every change is a threat to safety, so the first question that people ask on a network like that is, 'How likely is it that this change will kill an employee?'"

Faster, Stealthier Exploitation

Expect attackers to be stealthier and better prepared, and for them to focus on improving their automation and analysis capabilities, so they can monitor network traffic and build a better model of network weaknesses to find the valuable information in the network, says Vann Abernethy, senior product manager for DDoS mitigation firm NSFocus. "If you are a cyber defender, the guy who is attacking you probably knows more about your defenses than you do," Abernethy says.

The groups behind targeted attacks will be faster to turn vulnerabilities -- whether zero-day flaws or just unpatched software issues -- into live exploits. Researchers at security consultancy and testing firm NSS Labs, for example, detected attacks on the recent Android "master key" vulnerability (CVE-2013-4787) within days of the public report of the software flaw, says Frank Artes, the firm's research VP. The company has also seen growing innovation in exfiltrating data. For instance, some new exploits put stolen data in the padding used to fill out the packets in common communications protocols.

"We have seen extreme advances in getting exfiltrated data out," Artes says. "We are seeing really talented stuff. Complete violations of the RFCs, but at the same rate, brilliant."

While security firms often talk about an arms race between attackers and defenders, APTs sometimes give the attackers an edge, making targeted attacks hard to detect and even harder to stop. However, attribution of attackers will become more reliable as companies and nations gather more intelligence on the actors and agencies involved, says CrowdStrike's Alperovitch.

"They say you have to be 100% right all the time on defense, and the attackers only have to be right once," he says. "But for attribution, it's the reverse." He adds that a focus on fallible human adversaries, rather than just the technologies they create, will eventually give defenders a leg up.

About the Author

You May Also Like

Uncovering Threats to Your Mainframe & How to Keep Host Access Secure

Feb 13, 2025Securing the Remote Workforce

Feb 20, 2025Emerging Technologies and Their Impact on CISO Strategies

Feb 25, 2025How CISOs Navigate the Regulatory and Compliance Maze

Feb 26, 2025Where Does Outsourcing Make Sense for Your Organization?

Feb 27, 2025