How To Keep Your Users -- And Your Data -- Safe On The WebHow To Keep Your Users -- And Your Data -- Safe On The Web

Careless -- and occasionally malicious -- Web-browsing users might be the most serious threat to your organization's data. Here are some tips for keeping it safe.

May 18, 2012

Download the entire Dark Reading May 2012 Digital Supplement

Download the entire Dark Reading May 2012 Digital Supplement

On the Internet, nobody knows you're a dog. And increasingly, nobody knows you're a hacker.

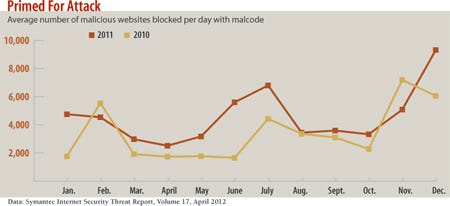

In the past year, attackers targeting businesses have started making more use of stealthy Web-borne attacks aimed at end users--specifically going after employees. Emails with malicious links, drive-by malware downloads, and error messages pushing fake antivirus scanners are all popular methods hackers are using to get through your company's front door.

Last year, 39% of email-borne malware consisted of hyperlinks, not attachments; that was up from 24% of email that carried hyperlinks in 2010, according to the latest version of Symantec's Internet Security Threat Report.

Why all the focus on the Web? Because it works. Over the last year, we've seen major breaches, at companies including Sony, RSA, and Zappos.com, and several U.S. military contractors that started with a few clicks on a malicious link. Employees need only make one mistake and they can open the door to targeted, sophisticated attacks and cause mayhem in your business.

"We are seeing the Web being a preferred medium for attackers," says Paula Greve, director of Web security research at McAfee, Intel's security software subsidiary. "It becomes a lot harder for the user to discern whether something in their inbox or on the Web is something that want to go to."

Hackers often use email scams to get people to click on a link that pulls in malicious content from the Web, fooling people into downloading malicious code and circumventing corporate information security measures.And the Web is increasingly being used as a medium to carry malicious communications between infected computers and command-and-control servers. Nearly half of all malicious software communicates out to the Internet within the first 60 seconds of infecting a computer, and about 80% of those communications use some form of Web protocol, says the Web filtering and security company Websense.

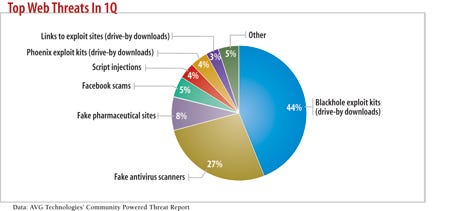

Exploitation using the Web has become easier with the availability of more advanced malware creation and distribution programs, such as the Blackhole and Phoenix exploit kits. In addition, it's getting harder for users to determine if a site is dangerous. The vast majority--about 61%--of sites hosting malware are legitimate, according to Symantec's Norton Safe Web service, which identifies malicious websites. And it's not gambling or porn sites that have the highest proportion of compromised pages--it's religious sites that do. In many cases, the site itself isn't the problem, but rather third-party content, such as advertisements, that carries the malicious attacks.

IT pros may look at the numbers and say, "How can this website be infected? It is a top-1,000 website," says John Harrison, group product manager with Symantec's security response group. "Well, it may be an advertisement on the site, and that makes our job difficult, because it may be one in 10,000 advertisements that come up in rotation."

Coping with these threats isn't easy, especially as hackers focus more on gaining access with browser-based and social network attacks, as well as efforts that take advantage of mobile device weaknesses. But there are steps companies can take to protect against these tactics.

Hackers Exploit The Browser

The browser is the gateway to online information, so not surprisingly, it has become the focus of attacks.

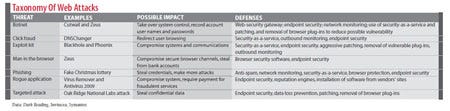

From the user's perspective, the most benign form of Web attacks are those that treat the end user as a resource--a click--and the browser as the way to collect those clicks. Such attacks don't try to infect victims' computers but instead to monetize and counterfeit their clicks, says Michael Sutton, VP of threat research for Web security company Zscaler. The DNSChanger malware, for example, would redirect ad clicks to non-Google services that would pay the cybercriminal money and send the user to a different product than advertised. These attacks focus on gaming the system rather than harming the user.

"It's a nuisance," Sutton says. "It uses up someone's time and resources."

More insidious attacks come in two flavors: drive-by downloads and fake antivirus software. Drive-by downloads infect a computer when a person visits a malicious website. Fake antivirus attacks convince users to run antivirus software that's really malicious software, fooling them into being unwitting accomplices.

These direct Web attacks typically consist of six stages.

The first, called the "lure," convinces the victim to do something--click on a link, go to a website, or run a program. Most of the time, the malicious program isn't on the site where the victim encounters the lure; instead, he's redirected to a second site--that's the second step.

In the third step, the attacker tries to compromise the victim's system by exploiting a vulnerability in the browser or a browser plug-in, such as Adobe Flash or Acrobat, or Oracle's Java. If the exploit is successful, step four is copying a program known as a dropper, back door, or downloader to the system. Step five, the malware then calls out to a command-and-control server to download more specific functions, such as a keylogger, spam software, or denial-of-service tool. Finally, the attacker starts using the system for the intended goal, usually to steal data.

"Whether that is Zeus trying to steal your banking credentials or something a lot more sinister, like a targeted attack that's going after your source code or your blueprints or whatever, it is still data theft," says Patrik Runald, Websense's director of the security labs.

By moving away from mass emails toward more Web-based attacks, criminals are putting their social engineering expertise to the most effective use. End users are wary of attachments. Rather than attempt to create a single attack packaged up into one email attachment, they make the best lure possible and then tailor the exploit to victims who fall prey to their social engineering.

The criminals behind the ZeroAccess rootkit, for example, changed their mode of infection last June. Instead of hiding malware in pirated and warez software, they began infecting visitors to websites using a drive-by download exploit kit known as Nice Pack. Like most modern exploit kits, the software checks the visitor's system and selects attack code to exploit vulnerabilities that likely exist there. The ZeroAccess attackers seeded advertisements and compromised websites with JavaScript to redirect visitors to the server hosting Nice Pack, says Jacques Erasmus, chief information security officer for security vendor Webroot.

"It cast a wide net and got a lot of infections," Erasmus says.

Social Threats

In addition to making more use of Web links, attackers are also using social networks to increase the chances of getting users to click on malicious exploits. As social network use increases, businesses are seeing an increase in malware, according to a Websense survey late last year. More than half of the 4,600 organizations surveyed saw an increase in malware as a direct result of employees using social media.

It's not hard to understand why. "Social networks are so much more powerful for the attacker," says Zscaler's Sutton. Anyone can send an email to a person's inbox, but social networking contacts are at least known acquaintances, and "that is so much more trusted," he says. Because social networking can deliver more potential victims, attackers are focusing on compromising those accounts.

"It used to be, 'I want to own your machine'; now it's, 'I want to control your account,'" Sutton says. "Your Facebook profile, your Twitter profile can be compromised, and that is of great value to the attacker."

A large contributing factor to the increase in social network threats is the widespread adoption of shortened URLs. Regular URLs give people a clue as to whether they are being sent to the wrong site. Shortened URLs remove that potential warning (see story, p. 9). Instead, people have to rely on the shortening services to catch malicious URLs, and those services vary in effectiveness.

A paper presented at the Web 2.0 Security & Privacy conference found that one service blocked 100% of spam links while two others blocked none. Seven other services ran the gamut, and the three researchers who wrote the paper concluded that "the spam detection rates for most of the services are not optimal."

Threats On The Go

For the most part, attacks on phones aren't easy to execute, and the benefits to attackers are unclear. Attacking a mobile device through its browsers is difficult, though not impossible. In addition, a compromised phone isn't easily monetized--yet.

But that's bound to change. Users are increasingly using phones for banking, storing valuable data, and connecting to the Internet, all actions that make the devices valuable to attackers.

While still a minor target, mobile devices are attracting attackers' attention because users treat them more cavalierly than their PCs. "It's about human factors, it is not really about technology," says Mike Lloyd, CTO at RedSeal Networks, a network security and management company. "It's because people use these Web capabilities and these mobile devices in a different way, and they have different expectations."

Still, mobile devices could become prime targets in the future. Known vulnerabilities tend to remain on the devices for months or even years. These devices aren't regularly patched because doing so requires firmware updates, and most mobile phone-makers or service providers aren't committed to supporting older phones with security updates.

Worse, most mobile devices aren't well secured, says Zscaler's Sutton. Many people wouldn't apply the patches even if they were released, and few run any security software.

"The guy on his iPad, well, he has nothing--he's sitting out there naked," Sutton says. Companies often make securing new technology an afterthought. "The vice president of sales will say, 'These devices are great, I'm giving 1,000 to my sales teams,' and then he looks at his CISO and says, 'Oh, by the way, go secure those,'" Sutton says.

(click image for larger view)

(click image for larger view)

CDI Flash Exploit

Don't Blame The End User

As attackers increasingly use the Web to get inside companies, it's easy to blame employees, but as the attacks get more sophisticated, that's unfair.

"Some of the phishing is so good that I would fall prey to it myself," says William Pelgrin, president and CEO of the Center for Internet Security.

A board member at browser security vendor Invincea received just such an attempted attack, via an email that appeared to be a notice from the American Institute of CPAs claiming that his status as an accountant would be revoked because of fraud charges. The email contained a PDF with a link to a website where he could respond to the charges.

The board member, who asked to remain anonymous, didn't click on the link in the email, but it could have fooled many recipients. "You can't untrain thousands of years of human psychology," says Invincea CEO Anup Ghosh. "That's why users will click on those links."

Much of the risk is driven by the uneven security of websites, a situation that IT can't control. When Symantec checked sites that use SSL certificates, which should have a higher level of security, 36% had at least one vulnerability, and a quarter had a critical vulnerability, according to the vendor's Internet Security Threat Report.

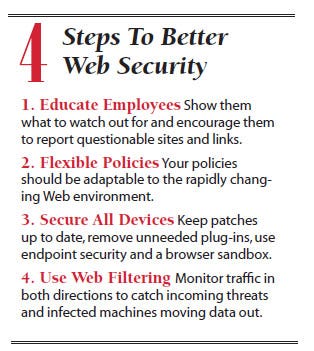

Some employees will be fooled by these attacks, but your first line of defense still must be employee education. Employees will undoubtedly encounter infected websites, so your company will be better off educating them to report emails with suspicious Web links and any other potentially malicious Web activity. Just don't count on them to act as a security barrier to threats, says RedSeal's Lloyd.

Moreover, make sure your company is using flexible security policies--a fixed policy can't adapt to the changing landscape of Web threats. For instance, some companies adopt an extreme "no social media" policy, hoping it will curtail data leakage and attacks through Facebook, Twitter, and other channels, but employees will find ways around those policies.

Be realistic, Lloyd says, because "the Web does change the equation. It changes users' behaviors, it changes expectations, and the corporation eventually has to deal with the fact that it's made out of people."

Secure The Device

In addition to educating employees, focus on hardening their systems. "When going up against zero-day threats, there are so many ways these things get written to bypass particular products, that trying to stop them is not at all reasonable," Webroot's Erasmus says. A layered defense is the best approach, he says.

Good security starts with patching, and reducing exposure to Web-based attacks requires keeping up with patches, especially updates to browser plug-ins. People often forget to patch these client-side applications, Erasmus says.

It can be difficult to automate the patching of browser plug-ins, and many plug-in developers don't update as often as they should. Given those realities, you can minimize the exposure of employees' systems by removing unnecessary add-ons.

Endpoint security products have gained notoriety for their failings, but they do serve an important role. They're useful because some threats are most easily identified by the actions they take on a victim's machine, and endpoint products can spot these.

One additional layer that can help with Web threats is a browser sandbox separating the browser from the rest of the system. While most browsers have implemented their own sandboxes, third-party software can put the browser in a virtual machine or add security underneath the level at which the browser runs. The trick is to put in a number of countermeasures and to react quickly to attackers, says Yaron Dycian, VP of products for Trusteer, which makes a browser add-on that helps secure communications between banks and their customers.

It's a battleground, he says. "There's no single defense, and there's no defense that will last forever. The single biggest priority is to be agile."

Host-based defenses that secure endpoints, like antivirus and browser protection, are popular but have shortcomings. Attackers are disguising malicious programs so that host-based scanners can't detect them using technology such as binary encryption and packers, which are compression utilities used to change the binary signature of malware and avoid detection by antivirus scanners. Man-in-the-middle attacks and exploitation of the browser can defeat many browser-based defenses.

These techniques, when paired with an attacker's Web-based infrastructure, let them more efficiently compromise users' systems. Attacks using email attachments are inefficient: Millions of emails are sent but only a few victims open the malicious attachments. Putting a link in an email message, however, lets the attacker focus on compromising the more promising targets--the ones that click the links and end up at the attacker's malicious website. A single spam campaign using attachments uses dozens of variants of malware, each packed in a different way to have a different antivirus fingerprint, but a single spam campaign using links can serve up a lot more variants, providing a unique version of the attacker's malware to each Web visitor, using exploits tailored to the victim's system.

"It used to be that you would see thousands of copies of a certain malware variant," says McAfee's Greve. "But the Web has changed that--now you can go to an infected website and get a different payload every single time."

Security Proxies: The Outer Walls

Increasingly, companies are looking to stop Web attacks before they get to the end user. Some companies filter the content employees can access online based on URL and domain reputation. That's a tricky corporate policy matter, but it does have a real security benefit. Of the more than 100 million Web requests that Symantec's hosted services blocked for clients in an average week of 2010, 99.96% were blocked for policy reasons, such as preventing access to gambling, entertainment, and porn sites. Only 0.04% of requests were blocked because they were malicious. That number may seem small, but a single infection can become the beachhead that lets an attacker get into your company's network.

Blocking malicious sites used to be easier: In many cases, the sites were in Russia, the Ukraine, and China. If you didn't do business in those countries, you could protect your systems by blocking traffic to those parts of the Internet. But that's all changed as the bad guys have moved their sites to the United States and Canada where they can't be easily blocked, says Websense's Runald.

It's also important to monitor traffic in both directions to catch threats coming into a company and infected machines trying to move data out. You must assume your company has been compromised and work from there.

Don't look at detection as an admission of failure; instead, make it a key part of your defenses. "The average company is far more infected than they realize," Sutton says.

The assumption that Web threats will get in suggests another defense: Use internal network segmentation to put a firewall between users and critical business assets. Otherwise, if employees have unrestricted access to important servers and data, a successful attack against one employee can easily turn into a company-wide data breach. Additional security around these assets can prevent that from happening.

"All user space is basically now exposed," says RedSeal's Lloyd. "You don't want that over in your fixed assets [such as servers] where you keep your data."

When dealing with Web threats, remember that the attackers are benefiting from many of the same advantages that you get from cloud services, particularly agility and economies of scale. For attackers, this means they can quickly gather information on targets to create more convincing lures, develop better malware, and tailor that malware to evade detection.

The best way to counter the trend toward more effective Web-based attacks is to be aware of the hacker's technology and strategy, and understand how they're helping attackers better defeat security measures. Then, be ready to counter the attacks with layers of responses discussed in this article that make it harder for attackers to penetrate your corporate network. That way, if the crooks do get in, you might at least keep them away from your most valuable servers and data.

Sidebar: URL Shortening Services Get Malicious

In the past, malicious links in email and on the Web were relatively simple to identify: If the link didn't match the domain that you were expecting to go to, it could be malicious. But the popularity of URL shortening services has done away with that easy check.

Shortened URLs make it "a lot harder for the user to discern whether it's something they want to go to or not," says Anne Aarness, a McAfee product marketing manager.

In late 2010, both McAfee, an Intel subsidiary, and Symantec identified URL shortening services as a potential problem. By May of last year, Symantec detected the first spammer-run URL shortening services operating under Russian domains. These early services were basic, just redirecting links to malicious sites.

Since then, criminals have improved their URL shortening scams by redirecting victims to multiple services and often starting with a legitimate shortening service. This approach makes it difficult to track down the bad guys and easier for them to circumvent efforts to shut them down. When a victim clicks on a legitimate shortened link in a spam email, the link is translated by the legitimate service into another link. The second redirect leads to the spammer's own URL shortening service, and possibly several more services, until finally being redirected to the malicious download site.

In July, Symantec documented a banking Trojan attack that used links from five different services in spam emails to convince users to go to a malicious website.

Attackers also use the identifier included in the shortened URL to track what content caused victims to click. Tracking these click rates could lead to improved spam campaigns.

Two-thirds of links posted to social network sites, like Facebook and Twitter, are shortened URLs, Symantec says. But most Twitter links aren't a problem. Another security company, Zscaler, scanned more than a million links and found only 773 were malicious. Only 0.06% of all the URLs tested were a security risk, says Julien Sobrier, a senior security researcher at Zscaler. That's much lower than some searches on Google, where Zscaler has identified 15% to 20% of the top 100 results as malicious. --Robert Lemos

About the Author

You May Also Like

Securing the Remote Workforce

Feb 20, 2025Emerging Technologies and Their Impact on CISO Strategies

Feb 25, 2025How CISOs Navigate the Regulatory and Compliance Maze

Feb 26, 2025Where Does Outsourcing Make Sense for Your Organization?

Feb 27, 2025Shift Left: Integrating Security into the Software Development Lifecycle

Mar 5, 2025

_vska_Alamy_.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)