Emotet Rises Again With More Sophistication, EvasionEmotet Rises Again With More Sophistication, Evasion

An analysis of the malware and its infection strategies finds nearly 21,000 minor and 139 major variations on the malware — complexity that helps it dodge analysis.

October 10, 2022

The threat group behind the Emotet malware-delivery botnet has resurrected the malware-as-a-service offering with more sophisticated countermeasures to foil takedowns.

According to a 68-page analysis on Oct. 10 from VMware's Threat Analysis Unit — based on data collected from several new Emotet campaigns in early 2022 — the group has learned lessons from the 2021 law enforcement takedown of the group's infrastructure. That includes creating more complex and subtle chains of execution, hiding its configurations, and hardening its command-and-control (C2) infrastructure. In addition, the group recently updated two of the eight modules to improve credit-card stealing functionality and its capabilities for spreading laterally through a network.

Overall, the research suggests that Emotet is continuously changing to make it more difficult for defenders to adapt and block the malware, Chad Skipper, global security technologist at VMware, stated in a press briefing.

"Emotet [has] embraced its role as a malware distributor, focusing more on advancing its technique for initial infection and relying on waves of spam emails that entice users to open up documents and click on links," he said.

The analysis of Emotet completes the malware-as-a-service group's resurrection, following a takedown in January 2021 by international law enforcement. Just the month before the takedown, Check Point Software Technologies had estimated that 7% of companies had been affected by the botnet. Law enforcement agencies gained control of the infrastructure and disrupted Emotet's infection and payload-delivery capabilities.

In late 2021, however, updated versions of Emotet and Conti began being distributed by another group, Trickbot, bootstrapping the once-defunct malware network and bringing it back from the dead.

The group behind Emotet — often referred to as Mummy Spider, MealyBug, or TA542, depending on different security firm nomenclature — typically uses waves of spam email messages and specially crafted messages to convince users to click on malicious links or open malicious documents. Access to the compromised machines is then sold to interested groups, who then steal data, install ransomware, or find other ways to monetize access.

VMware's TAU group analyzed data collected from the spam messages, URLs, and malicious attachments to classify the attacks into different waves, map the attacker's C2 infrastructure, and reverse engineer any delivered malware to gain insight into the attacker's activities.

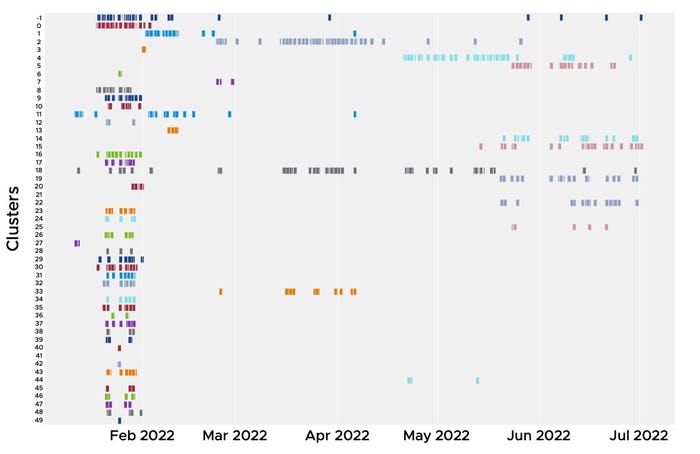

The top execution clusters for the Emotet malware. Source: VMware's Emotet Exposed report

The two waves analyzed by VMware in the report both used a malicious Excel document to infect systems, with the first — and smaller — wave using XL4 macro, while the second wave paired that with PowerShell. The researchers deconstructed the attacks into initial invocation variations and into execution flows finding 139 unique program chains and 20,955 unique invocation chains, which are variants made to make the infection look unique.

"Based on a new similarity metric, [the research group] was able to identify various stages of Emotet attacks with a number of initial infection waves that change the way in which the malware is delivered," VMware stated in its analysis.

Other recent updates include a module that targets Google's Chrome browsers to steal credit card information, and a second module that spread the infection to other computers using the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol, a common technique for hackers.

The threat actors also use significant anti-analysis countermeasures to attempt to hide the details of their C2 infrastructure, the report stated. The post-recovery version of Emotet has two major sets of infrastructure, which VMware calls Epoch 4 and Epoch 5, which have only a single common IP address between them. In addition, the malware could be executed using any of 139 different program chains, although 80% of the samples analyzed belonged to one of four different chains.

The most popular chain involved "a simple three-stage attack involving the execution of Excel and regsvr32.exe," the report stated. "The second most popular chain shows the same attack chain as the first but with an additional stage."

VMware found that the attackers' infrastructure led back to 328 different IP addresses, 18% of which were in the United States, with Germany and France accounting for a significant share as well. However, the servers hosting modules, updates and other payloads came from a different set of IP addresses, with the largest share (26%) hosted in India.

"[T]he IP addresses of the servers hosting the Emotet modules can be different from the IP addresses extracted from the initial Emotet payload configuration," the report stated. "[M]ost of the IP addresses extracted from the configuration were likely to be compromised legitimate servers used to proxy the actual servers that hosted the Emotet modules."

About the Author

You May Also Like

Uncovering Threats to Your Mainframe & How to Keep Host Access Secure

Feb 13, 2025Securing the Remote Workforce

Feb 20, 2025Emerging Technologies and Their Impact on CISO Strategies

Feb 25, 2025How CISOs Navigate the Regulatory and Compliance Maze

Feb 26, 2025Where Does Outsourcing Make Sense for Your Organization?

Feb 27, 2025

_vska_Alamy_.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)